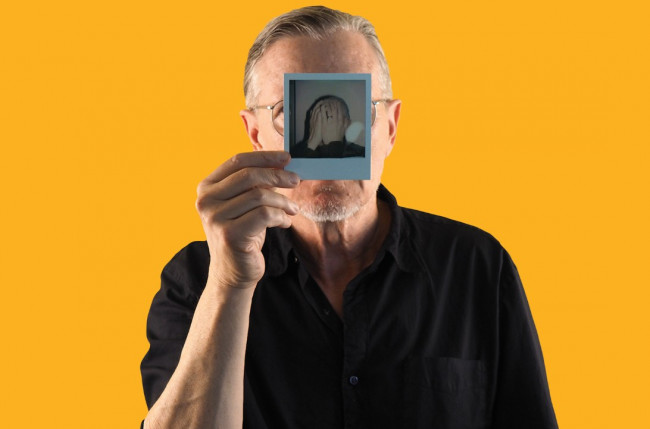

The Lost Interview: Michael Gira (Swans)

A few weeks ago Swans announced details of their sixteenth studio album, The Beggar, due for release on Mute on 23 June and also released the first single from the album, “Paradise Is Mine”

This is probably one of the last chances to publish an interview I did with Michael Gira back in late 2019 in support of the band’s leaving meaning album before it gets lost in the promotional necessities for the new album. As all the other Australian media outlets all published their 2019 interviews within a couple of days of each other, I decided to hold back for the Australian tour dates that the PR people had mentioned would be forthcoming. But then 2020 started. By the end of January 2020 it was clear that everyone was going to be re-thinking any tour plans and by early March anyone in the country was cutting short their tours and getting out and back to their homes until everything went back to normal. If we only knew then what was going to unfold over the last few years.

This interview has been sat here all this time waiting for a suitable time to publish it, even though the optimal time had long been and gone.

***

First formed in New York in 1982, Swans started life as an abrasive, bleak and brutal No Wave band, before transforming across the 1980s and 1990s into a sonically more diverse band, melodic, gentler and intricate, and with an increased use on acoustic guitar, even if the subject matter of the songs remained ominous and dark. After Swans ended in 1997, Michael Gira started Angels of Light before reforming Swans in 2010, releasing My Father Will Guide Me up a Rope to the Sky, followed by The Seer (2012), To Be Kind (2014) and The Glowing Man (2016). Swans fifteenth studio album, leaving meaning, was released in October 2019.

We spoke to Michael Gira about the post-2017 changes to the band, the involvement of Australian musical icons The Necks on two of the leaving meaning’s songs and not being afraid to fail artistically.

***

Collapse Board: I think the words you used were “dissolving the Swans line up”, the group of people that you worked with for the 2010 to 2017 period. Was there a specific moment or moments leading to where you knew you had to do make that decision?

Michael Gira: Over the final 18 months, I guess, of this tenure, there was nothing negative about it at all. We were all great friends and we had spent, I don’t know, approximately 200 days a year on the road together, as well as going in the studio every year. So it had just come to a point where we knew each other so intimately as a group that there really wasn’t a place we could go further. So we just decided that it was time to disband it. I have to say that for me, that seven years was the most elevating extended period of my musical life. I just felt like we accomplished some great things and being inside the sound that we created was a truly a kind of spiritual experience. I’m very proud of what we did and I love those guys, it just had to end. So I wrote some songs and then I decided to gather people together to help me orchestrate and perform the songs, people that I’ve known throughout the years. This is the way I worked in the 90s. From the late eighties into the 90s, with Swans, I would have different people involved in each project, so I decided to go that route again but I also involved those gentleman with whom I worked for the last seven years on the record, just not as a band. It’s a different thing when you sit down with some songs and you have this fixed group of people and then you decide how you’re going to play the songs, rather than have these songs and have various disparate musicians contribute their take on the material.

CB: So you had very defined ideas about each of the songs and who you wanted and what you wanted from it?

Well, I forged a core small group of people that would play the songs, the initial version of the songs, in the studio. That was the wondrous Larry Mullins, who played with Swans in the 90s, and also played with Angels of Light and now he plays with Nick Cave. Larry’s a tremendous symphonic percussionist, he was a child prodigy in fact, and so he can play any instrument, he’s a totally educated musician, so he played drums, symphonic, percussion, keyboards, all kinds of different instruments on this record. And I also had Christoph Hahn, who plays lap steel and he’s a great regular guitar player too, and he was in Swans and Angels of Light. And then I had Yoyo Röhm, who’s a Berlin musician and he plays double bass, electric bass and keyboards and he’s also an arranger, composer. So we had a good little core group with myself playing acoustic guitar and we built the basic grooves and structures of the record and then I gathered a whole plethora of other people to help orchestrate the record. I did have, I guess you could say a vision for the sound, but as always, once people start participating, I’m surprised and usually elated by their contribution and that leads to something else. I just kind of act like the head juggler actually, trying to forge the sound and then I mix it.

CB: I’ve always got the impression, and I might be wrong, but it’s always felt like Swans is almost like hard work, it’s very disciplined, and you spend a lot of time on the arrangements. What sort of personal attributes do you think a musician needs to have to successfully work with you?

MG: That’s hard to define, because it’s not necessarily skill. I choose people and what they do, the instruments they play, but also I picture them sitting in a room with me and playing music together. And if that doesn’t seem like it’s natural and honest and it’s a true thing, then I don’t contact them. So all the people I contacted on this record were, to greater and lesser degrees, friends. They are people that I just felt good about as humans and I was just hoping that they would have a sympathetic take on the music and that their own creativity would raise it higher. I don’t want studio musicians or people just to do what I say, that’s kind of boring. So I’m always looking to take things in a direction that seems unfamiliar and is exciting for that reason.

CB: You said that this was an approach that you used in the 90s, but in terms of making the decisions that you made about the personnel and how you’re going to do this album, did you ever feel like it was a risky approach that might not work out or did you always have confidence that it would?

MG: Oh, I never have confidence, I’m always ready for the next disaster! But I think that’s a good impetus to make good work as well, to just to be always kind of dangling on the cliff. And, I like that.

CB: You’ve worked with The Necks on two of the songs on leaving meaning, both of which, at least on the album’s Wikipedia page, have the music credited to them. Did they come up with them without input from you or did you provide guidance as to what you wanted them to do?

MG: I had recorded my acoustic guitar and vocals, at least scratch vocals, for those songs and I asked them to perform to that. One of the songs, the song that eventually Baby Dee ended up singing, my wife Jennifer sang as a guide for them. But no, the songs were written and structured, I guess you could say, and then I asked them to perform on them. Of course, as I mentioned with other musicians, I wanted them to elevate the process, which I think they did wonderfully. I love them, I listen to all their records and I just think that they’re an Australian national treasure.

CB: The Necks are amazing in terms of having the musical skills and mastery of their instruments to be able to do what they do each and every night they perform and not have it fall apart. It’s just some sort of magical alchemy. Given their constant improvisation, did you have any expectations as to whether it would be a successful partnership?

MG: I had hopes and I did not give them too much direction really. In fact, I don’t know that I gave them any. I could just kind of think “The Necks” and this sound appears in my mind. I don’t know how to describe that sound but if you’ve witnessed them live or listened to their records, I guess you would know what I’m talking about. Their ability to create atmosphere and this kind of unfolding journey of sounds is just amazing and especially with such minimal instrumentation. I recall seeing them live once and I was certain that there were some tapes happening or some kind of other instrument that wasn’t being played on stage, but I guess it was the harmonics from Chris’s piano. It was just amazing, they sound like angels. There’s a musician/composer named Charlemagne Palestine, who made a fantastic record in, I think it was the early seventies, called Strumming Music, and that’s him playing two grand pianos simultaneously, just sitting in between them. And a similar thing occurs, where through repetition and slight variations, the piano suddenly just takes off and releases this heavenly choir of sound that’s not being played, it’s just hovering above the pianos and it’s in the room. I’ve heard similar things with them too. And yeah, suffice to say, I think they’re absolutely tremendous.

CB: You’ve also worked with the Australian musician Ben Frost on this album. Did you meet him for the first time at the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival in Melbourne in 2013 or did you know him beforehand?

MG: I think we met before then at a couple of shows. We’ve been in touch and, as I mentioned, I picture people in the room with me, and he has a great atmosphere about him as a person. He’s just very generous and serious at the same time and super intelligent. So I pictured him on this record and I went to visit him in Iceland and I had the tracks basically recorded and, some instruction given, but not much really. I just wanted his ideas and then when he’d do something, I might make a comment, but mainly he kind of went for it and I think he’s great. He’s going to be playing as one of the members of Swans on the coming tour in 2020.

CB: You chose to revisit ‘Amnesia’ [from Swans’ 1992 album Love of Life] on this album. Was there any reason for doing that?

MG: I think I was including it in a live solo set for a while and just learning how to play it differently than how it had been previously recorded in the nineties. So it just became part of my repertoire and I wanted to record it, so I did. I liked the words, even though they’re just as obtuse to me now as they were when I wrote the time, I suppose. I was tangentially inspired for the arrangement by the Neil Young song from Harvest called ‘A Man Needs A Maid’. That’s a Jack Nitzsche production and it’s entirely grandiose and quite dramatic, and so I took that as a cue. It doesn’t sound like that song at all but there’s a certain kind of approach to the dynamics that might be similar, so that’s what I did.

CB: leaving meaning is the 15th Swans studio album, how do you look back on those first couple of albums you made which are so different-sounding to the work you do now?

MG: Well I don’t, mostly. What I did at the time, I was a completely different person then, I suppose. But you know, one thing led to another. Each record has a seed or a thread that can be drawn from to make the next record and so that’s why the music just keeps changing as it goes along. Each record, to me, holds the germ of the next one.

CB: I think you probably get asked this in every interview, about how you’ve said you’re driven by death, and I think there was another quote around “not wanting to live a pointless life and trying to make something happen”. If those are still the primary drivers for you, has it changed as you’ve gotten older?

MG: Well, you know, the great mullah of death is hanging right there, but then it always has been. I guess you become more aware of it as you get older and for me the sense of urgency is even greater to try to do something that holds a kind of truth in it, so that’s what I do. I mean, I don’t know how much hope I have of ever doing that, but that’s why I work, because I want to make something that seems undeniably real and sort of contains all that I am capable of doing.

CB: In calling the album leaving meaning are you thinking more about legacy that you want to leave?

MG: Not at all, it has nothing to do with that shit. Sorry [laughs]. It’s just my way of looking at the mind and consciousness and language. To me the most important things, the most important perceptions and the most vibrating sense of magic and urgency is before words and even before thought. And I guess in a way I’m alluding to that way of looking at things.

CB: It’s interesting talking to you because you talked up the musicians you work with and their skills, but you always seem to talk down your own musical ability, in terms of your playing ability. Do you see yourself more as a singer or a lyricist?

MG: Well, I don’t contextualize myself. As you said, I make things, and I trust in my intuition. I know that I’m not a skilled musician but I have a good sense of sound and I guess I’m able to follow my imagination. I’m not scared of failing, so I try things and I try to forge something unique, I hope. So that’s how I work.

CB: And you were always like this?

MG: Well, you know, I realised at a young age that I’m an artist. Then it was visual art, that’s all I cared about and I threw myself into visual art for quite some time. It’s not really a choice, it’s just what I do. Eventually that transformed into music. I became disenchanted with the art world and didn’t really want to be a part of that and at the same time punk rock was happening and that seemed to hold all these possibilities and it seemed so much more apposite and relevant to modern experience that I pursued that path and eventually found my own voice musically, and I guess literally.

CB: It made me wonder, because I know you went to art school, whether not being afraid to fail and the artistic drive was something you had before you went to art school or it was something that you learnt?

MG: Yeah, I mean to me it was integral to who I am and what I am. I still love visual art and I love music and I just follow the path, I just kind of forged my own world. I worked for many years in menial jobs and I was elated beyond description when I was able to finally start to make a living at music.

CB: As we’re almost out of time, I just wanted to ask how important the album artwork is to you?

MG: It’s very important. I’ve designed or art directed every record we’ve ever released. To me, it’s just as important as the music in a different way, it’s how the music finds a context and it also provides a juxtaposition that maybe doesn’t make sense sometimes but it just creates an oscillation in the experience that I like and so I’m always playing with that.

***

leaving meaning is out now on Mute/Young God Records

Latest news on Swans’ tour dates.