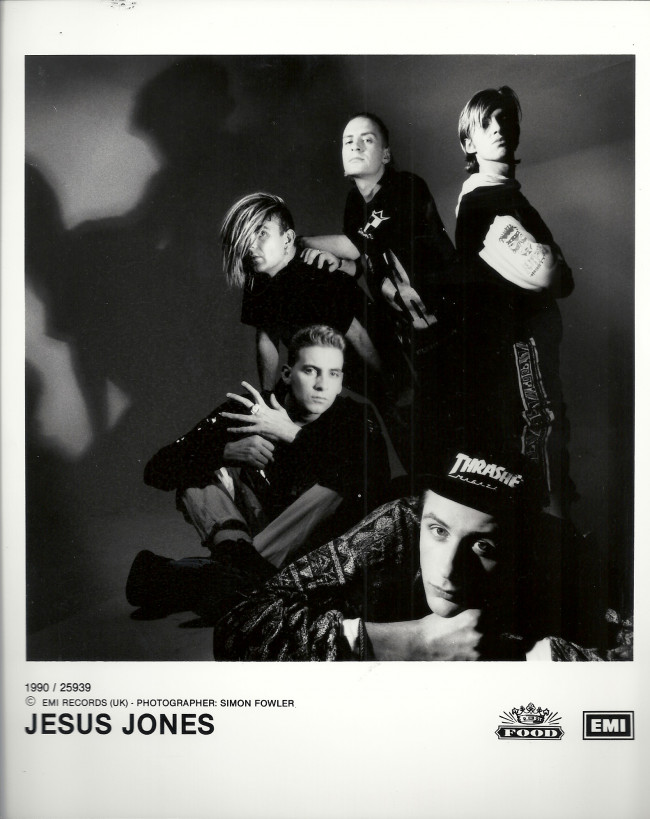

The Collapse Board Interview: Iain Baker (Jesus Jones)

You never forget your first music festival. Living less than 90 minutes away, I probably slightly lucked out that mine was Glastonbury, all the way back in 1990. A long weekend that changed my life, kicked off on the Friday afternoon with the likes of Lush, Galaxie 500 and Pale Saints. Later on in the day, Jesus Jones played.

My hazy 34 memory of the day has them playing in the later afternoon although the only online evidence I can find has them playing straight before the headlining Happy Mondays. I think Adamski played after them but, then again I’ve also always remembered James playing on the Friday and not the Saturday.

Back in the early nineties there was always a market stall selling bootlegs, including ones from over the weekend that they’d managed to quickly duplicate and print out the covers for. By the time I left the festival site on the Monday I had tapes of the sets played over the weekend by The Cure (a double tape set), who did change my life on the Saturday night, Sinead O’Connor, who was just amazing, (even if the tape includes the most out of tune note she probably ever sung) and Jesus Jones (and here it is, at least some of it, not sure if it’s the whole set).

In 1990, Jesus Jones, Lush, James, Happy Mondays were some of the bands playing a huge part of the soundtrack to my life as I left home, moved to the big city and started university. These were a handful of the bands that friends I have today first bonded over.

Ahead of an Australian tour with Pop Will Eat Itself, their first since they played with the Wonder Stuff in 2011, we spoke to Jesus Jones’ Iain Baker about the band’s formation, how the amazingly fertile UK music scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s gets overlooked, and how studying Latin can improve your life.

***

You’re a musician with a LinkedIn page, which is probably a rarity. And your LinkedIn page tells me “Latin, Classics, Classical Language, Literatures, Linguistics at Lancaster University”. How did you end up doing that?

Yeah, it’s quite a long story, really, I suppose. I mean, I was never the most kind of traditional person in my education, really. I just did what I thought I enjoyed doing. I just followed my heart and my head all the time. And when I was at school, Latin was never the most cool thing to be doing. But it was something that I found quite interesting and I actually found quite easy. Latin is something which allows you to think quite laterally about problems. The way that Latin is structured as a language, in that sense, it’s quite a creative thing to study. It allows you to be free creatively. Weirdly, Latin’s actually helped me in everything that I do now. Even though people will say, “Hang on a second, you’re a musician in a rock band. That can’t be anything to do with Latin at all,” but I think it is. Latin encourages you to think, as I said, laterally and creatively, and it allows you to think outside the box. When you are in a musician, in a musical environment, that whole thing is about thinking outside the box, so it’s actually a good fit. It doesn’t feel like it should be, but it is.

Your LinkedIn page also says you went to a comprehensive, which isn’t exactly known for dealing with the classics.

Yeah, it’s kind of interesting the way it turned out. It’s a long and dull story. We were quite a sort of a poor village comprehensive, but we were next door to a very upmarket private school, loads of people from around the world coming in, spending loads of money on fees, getting an amazing education. But it just so happened that the one thing that the public school didn’t have enough of was rugby pitches. And it just so happened that our school, the comprehensive school, actually had a couple of extra fields which had some rugby pitches in them.

So the posh private school said, “Can we borrow your rugby pitches? We need to teach our kids how to play rugby.” And being a comprehensive, we never taught our kids rugby. Nobody ever wanted to do rugby . They wanted to play football, but never rugby. And so we said, “Yeah, you can have our rugby pitches.” And the private school said, “OK, well, what can we give you in return? We haven’t got an awful lot of things that the poor kids are going to want to do. So we’ll just send you over some of our teachers.” And of course, I think as they were thumbing their nose at us and decided to send us Latin teachers.

Most of the kids in my class and my school did Latin for a year or two under extreme duress and hated it. I was one of those kids who was initially sceptical of it at first, but after a couple of years, I was like, “You know what? This is great. I like this.”

Yeah. I had to do two years of Latin and for reasons I could never quite understand, I was quite good at it.

Yeah. Yeah. I was the same thing. I was forced to do two years of it. And after two years, everybody else was like, “Oh, God, this is terrible. This is a dead subject. It’s not very cool.” And I sat down and thought about it, and I thought, “You know what? I’m actually enjoying this. And yes, it is dead language. And I don’t give a shit that it’s a dead language. I really enjoy doing what I’m doing.” So I carried on doing it.

And playing music always going on at the same time as well?

Yeah, totally. That was always a big component of what I did, even though maybe not playing music, perhaps, but just being a kind of musical obsessive. I’ve never been massively musically talented in a strict musicianship sense, but I’ve always been obsessed by it in a in a creative sense. And that means that, I was always looking at music, maybe not in terms of, “Well, I can make this, and I can replicate this,” but I wanted to dig into it and understand more about it in lots of different ways.

I wanted, not perhaps to understand the musical language, but I wanted to understand the creative impulse behind it. That’s why I ended up managing the band, because music, when it’s at its best, is a confluence of two things. It’s a confluence of talent and dreams. It’s a confluence of skill and ideas. And those two things look as though they come from different sides of the spectrum, but they both go towards creating a musical picture. If you look at all the great bands, they’re composed of, oh, I don’t know, the guitarist who’s got the chops and a singer who may not know anything about music, but is able to kind of live out the rock and roll dream He’s got the ideas and that creative urge and somewhere underneath him it will be a guy who’s got musical skill beyond anything else. And those two sides go towards creating great bands.

I know what you mean. Talking to musicians, the thing I’m most fascinated by is “How did you get here” and “What happened to you, especially kind of during your formative years for you to get on this path” and “How do you go about creating songs out of thin air, from a blank page.”

The thing that fascinated me about music, and it took me years to work it out is that music isn’t necessarily about music. Music is about understanding what it is that music does to you and makes you makes you so obsessed with it. And sometimes that isn’t actually the music itself.

There’s stuff which exists in an area outside music which orbits around songs. People say, “Why are certain punk bands amazing when it doesn’t seem as though they can play their instruments really well”? Because the thing that makes them great exists outside of music. And I didn’t understand that. People say, ”Oh, there’s there must be some primeval power in that.” And it’s like, “No, the power isn’t in there, it’s outside there. That’s taken me years and years to work out that that’s what I’m fascinated with. And there’s nothing wrong with that. Sometimes I think people look at music and they think they’re obsessed with it and they’re looking in the wrong place.

I read that you bonded with Mike Edwards [Jesus Jones frontman] over skateboarding and you met in a pub. Was that a completely random event or did you have mutual friends?

Completely and completely and utterly random. Utterly true. I was going to the toilet in my local pub in Pinner and a guy walks past me with a pair of, I think he said once, it was Vans. I don’t think it was Vans. I think it was Converse high tops. These days, if you wear a pair of Converse, it just means that you’ve bought a pair of Converse. Back then in 1988, if you wore a pair of Converse, it was like a secret sign. It was a signifier that you were a member of a secret society and that meant you skated. It was just so obvious.

I looked at this guy’s shoes and I said, “So you’re a skater?” And obviously he understood as much as I understood, because he knew those signs. And he said, “Yeah, yeah, I do skate, actually.” Back then there weren’t that many people that did it, so if you met somebody that shared similar values to you, there was a responsibility placed on each of you to try and bond a little closer. When you met somebody who was doing something that was so out of the ordinary, you cleave towards that person. You think to yourself, “Right, OK, fine. We’ve got to talk here. We’ve got stuff to talk about.”

So we did. That brought us together initially. And literally we exchanged phone numbers on a piece of paper. And I said, “Yeah, I’ll give you a call tomorrow.” And when I rang him up the next day, his flatmate literally said, “Yeah, he’s been waiting for you to call.” So I said, “Look, I’m going to my local skate park. I’ll be there in about an hour. And he was like, “Yep, I’ll be there. I’ll be there. Absolutely. I’ll be there.” And he turned up later and we went skating and everything has flowed from there. But there was no understanding initially that there would be anything kind of musical that would come out of it. It all happened very organically.

I was about to ask you how he sold the band to you for you to come in as the keyboard player but it sounds like it didn’t happen like that?

He didn’t sell it at all. People of our age at that time where we’re into skating, you’re kind of automatically into music. So we would talk about music when we were in the car going from skate park to skate park in those first months that we knew each other. When he brought up the subject of being in a band, there was no kind of like, “Well, you could be in that band, too.” He just said, “Well, look, I’m in a band. We’ve got some gigs coming up, blah, blah, blah.” And the first thing was that, “Well, OK, I’ll come along and see your band, you know, because I go and see other bands, so I’ll come and see your band.” And initially I just went to see the band and I just thought they were great. And even then, I never thought, “Well, I’ll be a part of this,” I just thought, “This is a great band.” I never had the idea to become involved and I don’t think Mike ever had the idea to involve me in it in any way.

The idea of that came from the late Andy Ross, who was the boss of Food Records. The band played a gig in Fulham that I went to just watch in the middle of the summer of 1988. And after they played, I was in the toilets with Andy Ross. And we’re both standing there at the urinals. And Andy looks over to me and he said, “They’re a good band, aren’t they?” and I said, “Yeah, they’re a great band.” And he said, “You should get involved.” And I remember I turned to him and I said, “Well, what the hell am I supposed to do?” And he said, “I don’t really know, but you should just get involved.” I think at that point, Andy looked at me and he saw somebody who was involved in a similar sort of youth kind of environment that Mike was in, being into music, being into skating, blah, blah, blah.

At that point, I was the manager of a skateboard shop so I’m dripping in the latest kind of skate clothes and I’m clearly involved in that particular culture. I think as somebody who appreciated those sides of culture, Andy Ross saw that and thought, “Well, maybe it’d be good to get that sort of angle into the band somehow.” I think he was coming at it from that side. He had no idea whether I could play any instruments, whether I was able to do anything and I don’t think he particularly cared. He was coming at it from quite a punk rock viewpoint, which said, if you’ve got somebody cool and you’ve got a cool band that could use another cool person, then why don’t you get that person involved? It’s that Sniffin’ Glue ideology, “Here’s a chord, here’s another chord. Now form a band.” And Andy Ross just thought, “Here’s a cool person, here’s maybe another cool person. Let’s put one cool person with another cool person and see if it works and see if something more cool comes as a result of that.”

Were the rest of the band ok with that, I think you were the last person to join?

The rest of the band, I guess, were OK with it because Andy Ross was coming at it from a creative standpoint, and I think the band trusted Andy Ross because he’d done that sort of thing before and he was obviously in the music business and could make things work. They were like, “Well, OK, if he says it’s a good idea, maybe it is a good idea.” In fact, as it turned out, it was a good idea. But nobody was to know that until they actually tried it and gave it a go.

When you did start with the band, what did you feel you were bringing to the band? Were you brining in your own of influences or was everything already there?

At first, Andy Ross just thought, “Oh, he’ll make this.” I think Andy Ross just looked at me managing a skateboard shop, with all the latest skatewear and whatever. And I looked good, I think I looked right. I think Andy looked at the rest of the band and he thought, “Well, they’re a good band, but maybe they don’t look right. Maybe they don’t look like they’re going to appeal to people like this guy, you know, because he looks like the audience and they don’t look like they perhaps reflect the audience yet.”

So Andy, I think, just looked at me and thought, “Well, if I bring him on board, maybe here’s a band that will end up looking like they reflect their audience,” which is exactly what happened. Because, of course, as soon as I joined, everybody said, “Oh, that’s cool. We’ll come down to your shop and you can flog us loads of clothes.”

But it happened all very organically. And it’s weird because the last thing that was ever brought up was, “Well, can you actually play any keyboards?” Because that was the initial thing. It’s like, “Well, maybe he can trigger the samples.” And they never even asked me, In fact, I think maybe a couple of years later, we were somewhere which had a piano and I sat down and I was actually playing the piano properly and everybody else in the band, there was this kind of double take moment where they looked at me and they were like, “What? What do you mean you can actually play the piano?” And I’m like, “Well, yeah, you never asked me.” It was never, ever a requirement.

I quite like the way that it happened, though, because it happened organically, but it happened against the flow of traditional the traditional way that musicians are assimilated into bands. The normal story is that there’ll be this moment where members of a band will hear somebody else playing guitar and they’ll be like, “That guy’s got the chops, that guy’s got something that we need as a band,” and that’s traditionally how the sound of a band is augmented. Nothing like that happened at all and I love the fact that it wasn’t a consideration at first and yet the net result is that the sound of the band ended up working perfectly as a result of it. It was it was just such a happy accident. Sometimes that’s the way that it should be. Like I said to you a few minutes ago, music is sometimes which exists outside of the musical sphere.

Outside of that musical sphere is the area where luck and chance and weird creativity and happy accidents exist. It’s nice that that bit outside made something work.

All my old vinyl is back in my parents’ house in Devon but I listened to the Jesus Jones albums for the first time in a while recently and was surprised at how fresh they sound, especially Liquidizer,

We went through a reissue program recently, when everything was put out again on vinyl, et cetera, et cetera. So you have to go through it and I think Liquidizer sounds bang up to date and it’s weird because there was a point in the ’90s where it felt like it faded from relevance and I’m not sure whether it has come back to relevance or relevance has drifted back to Liquidizer. But it sounds it sounds like it belongs again. I think one of the reasons for that is that it was it’s very much of its time. I think that of all the albums, even Doubt. Doubt has its kind of commercial foibles and the lingua franca of the album is quite commercial. And Perverse, too. But all of the albums were products of the time and they remain, almost defiantly.

I think that weirdly, if you create something which is like that, which is locked into its time, it gives it an internal honesty to its language. And that internal honesty is something which people look for more and more now. You really do look for that internal honesty and whether you like what we were doing as a band or not, I think that the internal honesty of the band at the time does shine through. You can’t say that we were faking it, you know. I think that the albums are the sound of a band doing what they wanted to do. There’s obviously plenty of people that didn’t like what we were doing, that’s cool. But you can’t deny that we were doing what we wanted to do.

And Liquidizer especially, I think, is the sound of that. I listened to it again when we were doing the reissues and I was like, “Wow, this sounds great.” Not because the music stands head and shoulders above everything else or whatever, but because it has that “We really mean it, man”-thing about it, you know? That’s why I like the album.

Given the technology on Liquidizer was so basic, how does the band look back on it? It is like, “Oh, we could do this so much better now with the technology that’s around now”?

Yeah, that’s a really, really good point. There is an absolute delineation between how I feel about the album and how Mike feels about the album. And I know to this day, Mike sits there and listens to the album and goes, “Oh, so trebly, there should be more bass on it.” He’s coming at it from the musician side, and the musician side is always saying, “Oh, I wish that it sounded more bassy and I wish that it wasn’t quite so sonic screwdriver in the side of your face.”

Musicians tend to be like that all the time. Peter Hook and Bernard Sumner about are always like that about the early Joy Division records, they always say, you know, “Oh, God, Unknown Pleasures, it should have sounded like Black Sabbath. Martin Hannett made it sound weird and strange and spacey. Everything was very dislocated. It didn’t have the raw Stooges power that we had as a band back then.” But of course, that’s why it’s so brilliant, you know. And so there’s that disconnect again between the dreamer and the musician. The musician says, “Oh, I wish it sounded more like Black Sabbath,” and the dreamer, the Martin Hannett out there is like, “No, it should have sounded like a weird UFO that landed from another planet.” So the dreamer in me really loves that way that Liquidizer has a sound all of its own and I know that the musician in Mike wishes that he could put more bass on it. I quite like it because it sounds the way it is because of the way that it was made at that specific moment in time.

Mike’s talked about the disillusionment setting in after Doubt was released, the disillusionment with becoming famous pop stars, was that shared between the band as well?

I think that was felt much more by Mike because he was the public face of the band. I think he got obviously disillusioned with and he felt that extreme pressure of responsibility. Responsibility to perform, responsibility to produce a constant stream of content which was always better than what came before it. And I think as the rest of the band, even if they weren’t writing the songs, even if they weren’t songwriters, we all felt the pressure, but in different ways. But Mike obviously got the brunt of it, because he was the press face of the band, the public face of the band. So he felt that disillusionment in different ways to us. Pressure mounts on bands in different ways. By the time we were touring Australia and New Zealand in May 1991. That pressure had risen to such a huge extent that the band basically imploded. We nearly split in May 1991 because of that pressure but we managed to kind of ride it out. The middle of 1991 was when it all reached a head.

With Mike being the primary songwriter, did that make it hard for everyone else to contribute their ideas?

Yes and no. Yes, it does in terms of the songwriting, because obviously Mike’s like, “Here are all the songs.” But I think in a sense that it frees everybody else up because, we don’t have to worry about the pressure of critical analysis of what we’re doing. We can just get on and be ourselves on stage. And yeah, you might not reap the rewards of the songwriting, but you don’t have that extreme pressure. And the pressure that it put on Mike at certain points was just nuts. I mean, it collapsed his first marriage and it led to an awful lot of darkness in the mid-90s, and none of us had to go through that the way that Mike did.

These days, in terms of how mainstream media deals with the 1990s, there was Grunge and then there was Britpop. To me, as someone who was 18 in 1990, there was so much great music in that 1988 to 1992 period that just gets overlooked or ignored. Do you get annoyed about the wide music scene you were in being slightly swept under the carpet?

I think it is sort of a little bit maligned now. At the time, definitely. As soon as grunge, then Britpop came along, there was a sense of like, “Well, we must now forget about the Wonder Stuff, which is hugely unfair.

If I can make a slightly pained analogy, that era, it’s a bit like Rocksteady, you know? I mean, like, Rocksteady is the most important thing in the development of reggae. Before that, you just have this kind of generic mass of Ska records and after Rocksteady, everything happens, You know, Rockers and Roots Reggae and eventually Digital Reggae and Dancehall. The entire way that reggae has been assimilated throughout the world, a lot of that, the musical heartbeat that reggae has to this day, comes from the sound of Rocksteady, it’s all buried in Rocksteady. Rocksteady lasts for like 18 months and that’s it. You can you can pretty much time when Rocksteady starts to when Rocksteady stopped.

You know, you get 18 months from like late ‘68 to maybe ‘70, middle of ‘70 and by the time ‘72 comes around, there’s no big Rocksteady records anymore. People have just moved on and they’ve forgotten all about it. But it doesn’t ever reduce the validity of those things and I think that over time, the validity of Rocksteady has just grown and grown and grown. I think that we were – I’m not saying at all that what we did was important in any way – but we were going through, we were living through, a stage in musical development that does play a crucial role in the way that independent and alternative music grew and developed and was given space to breathe throughout the rest of the ‘90s and the 2000s and onwards.

We were there at quite a fertile point. Like I said, I’m not saying, “Oh, without us, there is no whatever,” but it was genuinely exciting being at a musical point in time where so many things were happening and especially where so much cross-pollination was going on.

So if you look at that point between ’88 and ’92, there were loads of bands messing with different musical styles and putting things together and blending things. Occasionally, it works and occasionally it doesn’t work but that attitude that, “If you want to do it, you can,” that still persists and I think it persists because of us and our contemporaries. And again, yeah, I’m not saying, “What we did was brilliant, therefore, you now have these bands,” but we were living through a time where, for example, the rise in sampling technology, and the rise in early digital home studio recording was just starting. The fact that you can record things on a computer, the fact that you can sample other instruments and play them, those are now cornerstone foundational principles of music making in the 21st century. Every artist now, it doesn’t matter whether you’re working in R&B or folk or classical music or jazz or anything, you will be working with a laptop, with a digital audio workstation that contains elements of sampled music that you’ll be using to create your own music using the language, the style that you’ve adopted, like I said, be it jazz, classical, rock, indie, folk, whatever.

All of those come from foundational principles that bands between ‘88 and ‘92 were just starting to deal with. “Wow, we got Cubase,” “We can make music using a sampler, “We can use a drum machine,” “we can do this and do that,” there was so much of that going on and it pointed the way forward and it was genuinely exciting, I think, to be at a point in music where those things are happening for the very first time.

Although there were some bands I really, really liked, Grunge was looking back, back to Black Sabbath, Neil Young and so on, and Britpop was looking back to the 60s, The Beatles and The Kinks and whatever, but I always feel there were British bands in the late 80s and early 90s that were maybe not being futuristic and looking to the future, but building on what had come before, putting their own stamp on it and taking it forwards.

I think Britpop was this sort of, I’m not saying it’s a knee-jerk correction, but I think we’d had a number of years where bands were just banging on about the future all the time and whenever anything happens, the pendulum will undoubtedly swing the other way. That’s not to denigrate Britpop entirely. I mean, anything which gives the UK music scene the chance to develop its own musical language and do it with such passion is brilliant.

I tend to think that when I look back at the Britpop years, the initial part of it is perhaps not for me but you have this post Britpop thing, by the time you get to ‘99 onwards. I think things like the second Longpigs album, by the time you’re into the second Longpigs album, Mobile Home, Britpop has now mutated into this amazing sort of creative beast. That second Longpigs album is dark and inventive, and it doesn’t cling to a ‘60s Kinks aesthetic at all.

So Britpop definitely had the seeds within it to be able to move forward and translate it but I think the trouble with Britpop is that it did get into a bit of a cartoon when everybody thought that it had to be roundels and parkas and Knees up Mother Brown about British cafes and eggs and chips and beans, and that really wasn’t what it was all about.

Before we go, I probably should ask you about your upcoming tour of Australia.

Yeah, we haven’t really done that!

The last time you toured with was the Wonder Stuff, I think it was back in 2011.

Yeah, something like that. It’s a long time.

This time you’re touring with Pop Will Eat Itself. You were working in similar musical spaces, were you friendly with them at the time or did you see them as rivals?

Maybe we saw them as rivals initially, but I think all bands are like that. All bands are competitive when they start. I think our relationship with the Poppies has just changed into the point where they’re just great friends of ours. I DJ-ed for them a couple of years ago, we just go to all the gigs, we see them all the time, so I think it’s just going to be brilliant to be touring with them. When you get to this point in your careers, you look for those things that make you do things because they make you happy. Touring with the Poppies will make us happy, coming back to Australia will make us happy. It’s great to get to that point in your life and your career where you have the ability to do something solely because it makes you happy. It’s an honour and a privilege to be able to do things for that for that very reason.

***

POP WILL EAT ITSELF and JESUS JONES Australian Tour Dates

Thursday February 29th BRISBANE, The Triffid

Friday March 1st SYDNEY, Manning Bar

Saturday March 2nd MELBOURNE, The Croxton

Sunday March 3rd PERTH, Freo. Social