Ardent Mythology: Following The Libertines

By Alexis Late

A lot of well-worshipped musicians tend to have a web of mythology encompassing them. Sometimes it’s created by scandal loving press and is, not surprisingly, flawed or exaggerated; sometimes it’s unearthed by fans through intimate obsession, or woven by the artists themselves, as they make their manifestos public. The Libertines were a band made up of all three, a mixture of galvanising and detrimental. As some of you know, they broke into the British indie rock scene in 2002 after being signed to Rough Trade. This happened amid heavy press coverage on the ‘garage rock revival’ with bands like The Vines and The Strokes being lorded as the new saviours of rock by hungry opportunists caught up in cashed up taxonomies like grunge and Britpop.

Before that, though, they were a band that inspired the formation of a strong community of fans even in their dawn days, performing guerrilla gigs in their lodgings for the love of it, and becoming close with punters. Inevitably, after the interest of big guns, they became the darlings of the British music press, and this was before NME desperately championed any band that so much as looked like The Libertines, in the process damaging their credibility as a Band That Mattered, especially when so many equally good bands were left in the margins.

For me, a would-be poet who spent the mental wilderness of teenage life either immersed in the call to arms of punk rock and its offshoots, in the most controversial novels I could find, or in 18th century Romantic poets who conveyed a sense of magic during a mechanical age, The Libertines were a band that captured what I thought was a strange longing in just me, a yearning I didn’t fully understand until I heard the barraging head rush that is the song “Time For Heroes”. In the same way that Patti Smith captured everything I was feeling about authority in the first thirty seconds of Horses. And the way that Bikini Kill seemed to be channelling the anger and frustration at patriarchal and misogynistic bullshit straight from my guts. The track is a banger from their debut album Up the Bracket, produced by Mick Jones, whose own early albums – along with The Slits, The Raincoats and X-Ray Spex – had formed my understanding of punk rock as a fifteen year old. Four things stood out from hearing “Time for Heroes”:

1. the song was a modern call to arms disguised as a love song

2. it was a kaleidoscope of Brit rock thus far, from 70s punk to socially aware Britpop numbers

3. it was poetry, a doffing of the hat to the Romantics and 19th century aesthetes

4. that Peter Doherty, Carl Barat, John Hassell, and Gary Powell, were – at that point anyway – genuine.

I was liable in those days to label bands as either phony or genuine, which is rather black and white thinking and an indication of Salinger’s influence, but it only applied to what I felt for myself, not for others, and really, I only had so much time and I couldn’t be bothered to generate energy for bands that were concerned only with entertainment, you know what I mean? “If you’re here because you want to be entertained, please go away”, Sleater-Kinney warned in 2005, but two years later Sleater-Kinney were not around, and I was looking for something to fill the abyss.

It had been three years since The Libertines disbanded, and I had spent much of the early decade too preoccupied with dead heroes to notice them. They were a distinctly British band that didn’t inspire as much devotion in sleepy Perth as they did in the UK, and asides from being struck by their second album cover in music magazines where I skipped to articles on the legacy of punk rock and the Seattle/Olympia scene, I missed their explosive downfall. Why did I become obsessed with The Libertines when they had just disbanded, like Sleater-Kinney? I guess the answer is, mythology. When they split they weren’t just a garage rock revival cliché that got over-hyped and burnt out in a sweltering mess of drug addictions and infighting.

They were birthed from an ardent mythology that would speak to countless people who felt like they could finally admit that yes, they were a Romantic in a digital age, that they liked poetry AND punk rock, that revolution could happen, even if just in a musical sense, and two fingers to class and socio-economic status, because ‘we’re in a class of our own, my love’ as the lyric in “Time for Heroes” goes. Such lyrics are universal (if you think there are no class divisions in Perth, think again) but also very British, reflecting sectarian ugliness lurking underneath fabled cities of literature and art. The Libertines unearthed the ugliness and created a romantic yet defiant response to it. If you can’t cry or rage, why not make music for the other misfit stragglers that you come across?

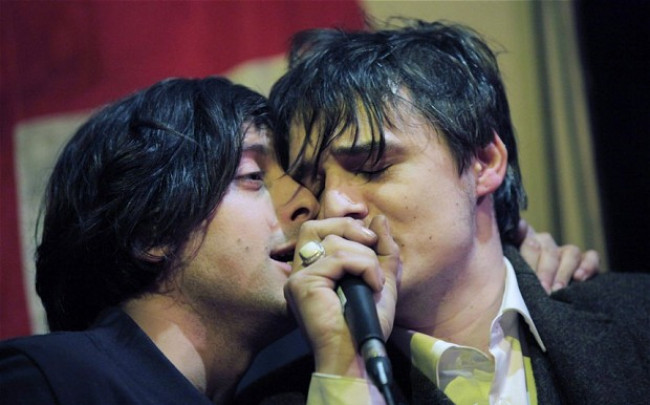

Peter Doherty and Carl Barat, the much speculated-about front men who co-wrote the lyrics and famously shared microphones, had lived together in a flat they dubbed ‘The Albion Rooms’ in East London. Peter was a Britpop obsessed army brat who had won a poetry prize at sixteen and moved to the big smoke to study English Literature, and Carl was the guitarist son of a commune living hippy, already two years into a Drama degree. They bonded over a love of literature, old-school comedies, and a burning desire to revolt. In doing so they stirred into life not only a band but also fables and yarns that sustained them through their poverty years, and would later sustain their heartbroken fans, dreams of ‘the good ship Albion sailing to Arcadia’, a Blakean vision bent on a Shangri-La where there were no severe rules or constraints. Thus their name.

These fables were myriad, ranging from their versions of British classics like Chas n Dave routines that they would bust out during interviews, celebrating a cheeky London spirit that fans emulated, to foreshadowing renditions of Vera Lynn’s ‘We’ll meet again’ in tour buses, and allusions to the Cockney 50s comedy ‘Tony Hancock’, as well as tales of their friendship. For example, an interview where Peter and Carl admit they were like ‘one legged men’ before they met each other, Peter’s recollection of learning the guitar by being ‘sat at Carl’s feet’ and a popular story of how Carl thought Peter’s early request of a tab for The Smiths’ Charming Man was a request for Charmless Man by Blur. There were also stories of police raids on The Albion Rooms, to break up the boisterous early gigs, where Peter earnestly told them his occupation was being a poet, and their time living above a brothel, and of trying to be rent boys. And then there were the darker bits.

“It was either the top of the world or the bottom of a canal,” a depressed Carl told Peter in those early days, a quasi suicide-pact admitted on forums to become another part of the saga. I came in late, admittedly, when the ship had capsized and the openly feuding front men had formed new bands, but I was attracted to the defiance and earnestness of The Libertines, everything they stood for and had tried to articulate. I joined a group of fans on the Internet who shared stories, posted rare photos, dug up old demos, and remained faithful to the dream – that “if you’ve lost your faith in love and music the end won’t be long” – which we all kept alight, huddled over the meagre flame. A lot of us remained hopeful that Peter and Carl – especially Peter, as he spiralled ever downwards and became the centre of fucked-up media frenzy – would absolve themselves and get the band back on track.

On a lighter note, this Internet devotion also spawned some surprisingly intelligent fan-fiction based on the nature of their relationship, which occupied imaginative fans through the dark years of drug offences, jail terms, bitter comments and media ugliness. Stories that fleshed out the boys’ early days and the passion that kept them together, or of reunions set in the near future where they reconcile, amid their separate band commitments. There was a lot of romance. While not explicitly calling themselves a queer band, The Libertines were proud of being ambiguous and sometimes androgynous, and didn’t mind blurring outdated lines. They were libertines, after all. I loved this about them, loved that, like Bowie, Manic Street Preachers, Placebo, The Cure etc., they scorned the macho strutting of bands like Oasis or Kasbian, for example. I mean, as if we haven’t seen enough of that, right?

In the meantime the NME decided to openly flaunt their desperation to find the Next Big Thing and flog the hell out of it, focusing on any band that sounded or looked like The Libertines, and reporting like a sycophantic village gossip on every action Peter made – like The Scum or The Daily Fail – making one rather tired of it all. Some people questioned, are they worth it?

As much as I dislike the NME, I thought so. The Libertines didn’t inspire half-heartedness. You either liked them or you fucking loved them, and this probably said more about us than it did about the band. For me, a twenty-year-old punk rock enthusiast yearning to be a poet but also embarrassed about it, this was a band that represented to me what music – and writing – could be. That it could be incisive, romantic but also realist, defiant, socially critical, witty, a medley of frenzied riffs and passionate lyrics that you could dance along with but also start a revolution to. Their best record Up the Bracket was the unabashed love child of The Smiths, Buzzcocks, X-Ray Spex, The Slits, The Clash, The La’s, among others. It featured the frenetic interplay of volatile guitars that brought to mind Sleater-Kinney, the punk drums of Gary Powell, the rooted bass lines of the ever calm John, and a song-writing duo whose influences were so varied and so influenced by literature that it made me palpitate.

Clear punk rock numbers like “Up the bracket”, “Horror show” and “I get along” emit a whimsical lo-fi production, yowled vocals and desperate tales, following a pattern set by early single “What a waster”, a song that didn’t get much radio play due to its expletives, a glorious, raucous tune about, well, wasters. Then there are surprising ballads like “Radio America” and “Death on the stairs”, revealing Peter’s poetic sensibilities (also unveiled in music award clips where he recited poems by Siegfried Sassoon).

“Death on the Stairs” to me is one of the most perfect songs ever written. A stuttering melody that reaches into your cranium, with Carl’s guitar plaintively echoing every verse, and Gary’s mad emphasis on the toms and some of the best lyrics, in my view, ever written. Before Peter was a vilified drug addict he was a poet, and this is evident on the track, the title derived from a joke between the pair that they would die on the rickety stairs that led to their flat. The deeper inference was – especially for Carl – that they would die in the class they were born into, that they’d never be able to rise above it. This is embodied in the line:

There’s a little boy in a stairwell who says “I hate people like you”

Got matches and cable TV, half of less than 50 p

The determination to escape the past and start anew comes forth:

Don’t bring that ghost round to my door

I don’t wanna see him anymore

These sentiments are echoed in “Tell the king”, where Peter reminds Carl of his value:

Even now there’s something to be proud about

You come up the hard way

And they’ll remind you every day

You’re nothing

As for the breakup of said relationship, it’s all over their self-titled second album, a self-confessed airing of dirty laundry, an album recorded in disparate takes with a barely coherent Peter and bouncers hired to keep them from physical violence. This is not to say the songs aren’t good – some of their most incisive lyrics are from that album. In “Campaign of Hate” they touch on issues of social division, discrimination and phoniness:

Do you remember why you came?

Not to play follow the leader

Poor kids dressing like they’re rich

Rich kids dressing like they’re poor

White kids talking like they’re black

Well I tried it with Charlene

And I spent 3 days on my back

In the short fast burst that is “Arbeit Mach Frei” they call out hypocrisy:

Her old man

He don’t like blacks or queers

Yet he’s proud we beat the Nazis

How queer

And in tracks like the B-side “Dilly Boys”, they stomp on the cliché that is male posturing in rock, singing unashamedly from the point of view of male prostitutes, in the vein of Morrissey and Placebo:

Me, I’m just a dilly boy

fresh flower pressed Piccadilly boy

Hands on hips, pout on lips

Meat rag jack like a dilly boy

The album is about the breakup of a shared dream as well as a relationship, in songs like “Music when the lights go out”, “Can’t stand me now” and “What became of the likely lads”. It’s an album anyone who is falling out of love – with a person or a dream – can relate to. I don’t need to go into the messiness that ensued, but perhaps the best thing that happened was the dissolving of the band at that point. If they had continued and then trampled all over their own mythology there probably wouldn’t have been enough fans left to welcome them back in 2010 and 2014.

And yes, I was obsessed. The years of listening to dead heroes, and seeing American Northwest punk rock as a revolution that was cut short, had made me tired of feeling tired while I was still young. I needed to believe that music in these post post-modern times could still be hard-hitting and unafraid of not being played on the radio – and I’m not saying the Libertines were the only such band. Of course they weren’t. It was just that they were one of a few that stood out for me, capturing an anarchic spirit that I positively salivated for, at the same time reminding me in a Lennonesque and Patti Smithish manner of how music and love can overcome shitty circumstances.

For someone suffering from badly disguised depression, it was what I needed to hear. All through my teenage battle with the disease, I couldn’t see a future for myself, and bands like Alice in Chains, Bikini Kill, Hole, Nirvana and L7 peeled away the layer of smiles that I cultivated in order to survive among ‘shiny happy people’, giving voice to my disillusionment. On the cusp of my twenties, though, a brand new decade stretching out scarily before me, I wanted to believe that my desire to write could see me through, and that music could keep me going in the meantime. I didn’t want just anguished honesty from songs – I wanted hope. I wanted something to believe in. The kind of raw hope that proves a romantic dream can result in a kick ass record. I wanted the comfort of mythology, fervent stories for dark nights, and The Libertines provided.

Despite all of this, I didn’t fly to England for the 2010 comeback in Reading and Leeds (I had gone over in 2008 to see Peter solo, Carl and Gary with Dirty Pretty Things), for financial reasons as much as for the fact that I wasn’t sure the reunion would go anywhere. I was too invested in the band to fly all that way and be let down. I didn’t know if they were just cashing in, which they probably were to some extent. I was more interested in a Riot Grrrl resurgence that was starting to happen, and as someone once said, fresh water bubbles up again elsewhere, as most things sooner or later become stale. However, four years later, when they started definite talks about a new album, I kept my eye on things. Soon enough, Peter completed what appeared to be a successful rehab stint in Thailand and John, Gary and Carl joined him there, signing a record contract for a third album. The rift between Peter and Carl seemed finally healed.

And now, in mid 2015, they have released a single, from their forthcoming album Anthems for doomed youth, the title a nod to Wilfred Owen’s lament for fallen soldiers. As you gather, I have expectations for this album. It’s been ten years since their last release, and they’re obviously not still twenty-somethings with stars in their eyes. They’ve achieved but they’ve also not achieved. They’ve got disillusioned fans to win back, they’ve got their own disillusionment to get over. Will they live up to their mythology? Is the mythology even relevant to them these days? Not the drug-fuelled lifestyle the media brandished in burbling hyperbole, but the early ideas of poetry and friendship that fans looked up to. It’s hard to divorce them from it.

Still, I felt the lack of it on “Gunga din”. The song lurches forward with a jilted reggae influenced beat that reminds one of The Clash’s later work, but has none of the unpredictable guitars or the energy exemplified on The Libs’ previous records . It seems hastily slapped together. There is a weak literary allusion not fully explored, the title being derived from a poem by Rudyard Kipling, about a British soldier who realises his servant Gunga Din is a better man than he. This is the spirit behind the song, I suppose – the realisation that, to both Peter and Carl, it seems the other is a better man and has been all along. It is a space where they recognise their faults, past and present. They’ve matured in some ways, perhaps not in others, and the punk brazenness that marked their early songs is not present here. The music sounds rather generic indie.

Personally though, I like that, after ten years of various battles, they’re still alluding to poetry. I think that literature and history is a wealth of material that musicians can use, and some do. And part of the mythology that revolves around The Libertines involves their unapologetic love of verse, so perhaps the good ship Albion has still risen from the depths of the sea. As to whether it can sail, one can’t know until the album is released in September. “Don’t look back into the sun” was one of their refrains in times of yore, so perhaps the newly returned will be at their strongest if they move forward with a new vision instead of trying to rehash past glories, as some people want them to. Sleater-Kinney did a blisteringly good job of it earlier this year, so maybe they can too.

As they once sang, ”there are no good old days – these are the good old days”, so I damn well hope you prove it, boys.

Related link:

The Singles Club – Libertines / Velociraptor